Firstly, welcome to my new blog! (Or is it a “newsletter”?) I’m going to go with “blog” because I’m not exactly sending you weekly news reports here. These are my unvarnished thoughts on the world we live in - covering international politics, trade, economics, national security, the whole gamut. They are thoughts that are (at least in my opinion) far too unconventional and provocative to make it to my more staid and formal columns in the world press (yes, too “unconventional” even for me).

I know what you’re going to say here: “Don’t you already rant about these things on Twitter?!” Yes, I do. But as a boring, nerdish guy with a penchant for using (too many) words, I finally grew tired of Twitter’s draconian character limit. I wanted to drone on for a bit more - perhaps a lot more - on some issues that I think I must explain at greater length.

I write this blog very differently from my other, more formal columns. Each of these weekly posts is going to be rather more informal (although, even as I type this, Grammarly tells me that my text sounds “formal”). They will contain multiple issues (perhaps 2-3, sometimes 4) that I’ve been musing over during the week that’s gone by. These issues are going to be very varied; I will definitely be jumping from country to country, and sometimes, they might not even be related to each other. But the idea is to give you a sneak peek into my subconscious, and what I’m pondering over during the week, even as I watch cricket or binge Netflix.

So, let’s get started!

National security; whose security?

I’ve always felt that “national security” is the most misused and vaguely defined term in international affairs — a field of study that’s infamous for misused and vaguely defined terms. Everybody is always talking about it; putting it on their job descriptions; citing it to tell you why you can’t ask them uncomfortable questions.

Literally speaking, “national security” should be fairly self-explanatory: it’s about the security of a nation. To call COVID-19 a “national security” issue is a fair call; after all, it has managed to shutter economies, overwhelm hospitals, ruin entire families by wiping out their loved ones. All of these things can harm the “security” of a nation at some point. They can lead to poverty, civil strife and political instability, as angry people storm out into the streets.

But when most writers, journalists and academics talk about “national security”, they’re really talking about the security of governments, not their people. That’s why when people protest for their rights — or ask for autonomy so that they can govern their own provinces — they are deemed “national security threats”.

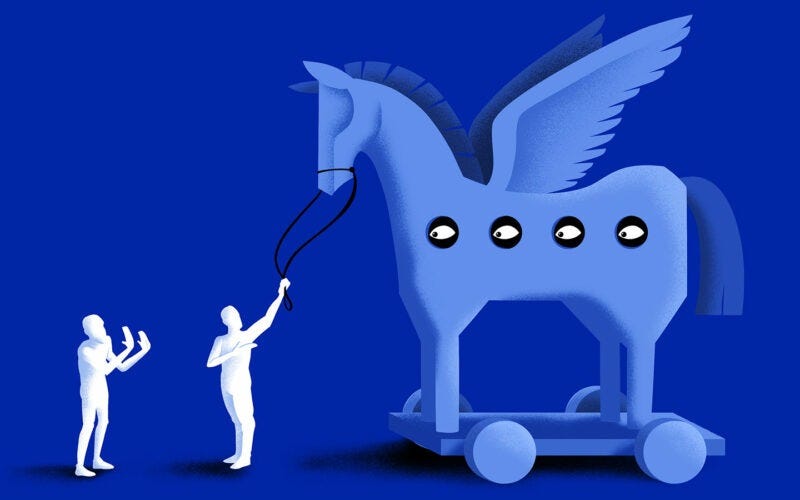

This week, I finally landed on some fairly concrete proof for what I’m talking about. After a year of investigation, the (“failing”) New York Times published a spy story that makes James Bond and Ian Fleming sound outdated and dull. For years, they wrote, the Israeli government has been selling Pegasus — the notorious spy software that can crack into your iPhones and read everything you’ve ever saved on it — to countries all over the world, in return for influence.

The attractive thing about Pegasus is its ability to crack encrypted conversations stored on smartphones. Apparently, most spyware cannot do that quite so easily. Unlike most hacking software, it doesn’t need the unsuspecting victim to click on a not-so-subtle link in order to penetrate their device. All it needs is your phone number and NSO’s engineers (that’s the firm that makes Pegasus) will be able to walk into your world.

The clever thing about Israeli foreign policy is that it knows that many governments want Pegasus — to tackle everybody from suspected terrorists to pesky journalists — and it used an export-licensing system to decide whom NSO can sell it to. According to the Times, countries like Mexico and India signed deals with the Israeli government to purchase Pegasus and, in return, they pledged Israel political and diplomatic support at the UN and elsewhere — especially U-turns on their (previous) support for Palestine. Some of these countries then turned around and began using Pegasus on dissidents at home, with — of course — the Israeli government’s tacit approval.

This sounds like a great deal for Israel’s “national security”. Israelis should be thrilled that their government used the spyware trade to win global support in the conflict with Palestine. Except, as recent reports show, the Israeli government didn’t just sell Pegasus to other governments; it also used Pegasus on its own people.

So, for years, governments around the world have been selling each other sinister software to expand their own influence at the cost of their people.

Of course, governments have been selfish for centuries, but what’s new here is the quality of weapons at their disposal. Arms exports have always been a part of how countries build their influence, which is why they showcase them at the national day parades. But fighter jets and centrifuges can't wage secret wars on one’s own unsuspecting citizens. Cyberweapons can.

That brings me to the original question on my mind: What is “national security”? Does “national security” only mean protecting the government from threats against itself (both internal and external)? Shouldn't the primary objective of national security be to protect the rights of citizens? Can the interests of the government sometimes run counter to the interests of citizens?

I think we've come to a point where, in national security studies, there has to be a conscious distinction between the interests of the government in power and the rights/interests of their citizens. This should be done even for democracies, where governments are seen to represent citizens. After all, no government wins all (or even most) votes.

Putin’s gamble and the dilemma of nations

I have to admit: Putin intrigues me plenty. He’s an unusual throwback to the quintessential Cold War-era Bond villain. What he does at any given point in time appears to be the culmination of years of careful planning and strategy, all leading up to that point. Of course, that may or may not be true (and no Bond villain ever succeeded). But his ability to exploit psychological weaknesses in the enemy is worth writing about.

Let’s talk Ukraine, for instance. In his Washington Post column this week, Fareed Zakaria opined that Putin’s decision to annex Crimea and unsettle eastern Ukraine was suicidal. Those regions are home to ethnic Russians whom Putin has been trying to win over. But by tearing them away from mainstream Ukrainian politics, Fareed argues, Putin has ensured that no pro-Russian leader can ever win power in Ukraine: “Putin took millions of pro-Russia Ukrainians in Crimea and Donbas out of the country’s political calculus. (Those in Donbas don’t vote in Ukrainian elections because the area is too unstable.) As a result, a Ukrainian politician estimated to me that the pro-Russia seats in Ukraine’s parliament have shrunk from a plurality to barely 15 percent of the total.”

But even as he pulled away the pro-Russia folks out of Ukraine’s politics, Putin managed to drive a wedge between them and the rest of Ukraine. After Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union, Ukrainians were divided between pro-Russia separatists and Ukrainian nationalists. But compared to any time in the past, the two sides hate and distrust each other far more today.

In practice, Ukraine is already two nations today — divided between Ukrainian nationalists and ethnic Russian separatists. Even if there is no war — and Ukraine does not split — one wonders if the two groups will be able to live together peacefully. If Ukraine splits, it will result in two somewhat more homogenous (maybe stable) but hostile neighbours.

Ukraine’s predicament is very common. Many countries everywhere are struggling to make peace between different religious/ethnic/linguistic communities. Sometimes (or oftentimes), there is a civil war and the communities break up into two (or more) separate nation-states.

All this made me ask myself a question that I don’t have an answer to: Would you rather have two monoethnic, hostile neighbours, or would you have one large country full of warring tribes?

Let’s consider India and Pakistan, for instance. The Partition of British India resulted in a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan. For years, Muslim extremists have had no trouble winning power in Pakistan, and Hindu extremists win power easily enough today in India.

But if Partition had never happened, how different would undivided India have been? There would likely never have been a Hindu-nationalist government in an undivided India because Hindu chauvinists would never have won enough votes in the many Muslim-dominated states (which are today in Pakistan). And the same goes for Muslim extremists: they would never have won power because no Hindu-majority state would ever have voted for them. So, in some sense, Hindus and Muslims could have acted as a check on each other’s worst impulses — at least making sure that religious chauvinists could not capture power nationwide.

On the other hand, the peace may well have been tenuous, particularly in the aftermath of infighting and communal rioting. Some Hindu-majority states and Muslim-majority states could have been polarised and angered enough to vote madmen to power. And the frustration — on both sides — that their favourite madmen aren’t able to win power at the national level could have led to more rioting and civil war.

The most interesting test case for this problem is perhaps Lebanon, where the president is Christian, the prime minister Sunni, and the speaker of parliament Shia. By giving everybody a slice of the pie, the Lebanese hoped that they can find a way to live with each other. Yet, all that that has led to is an incompatible and corrupt government, which has continued to fuel protests and civil strife to this day.

Anyway…

If you made it this far into my rant, that’s all I’ve got time for in this first installment of my new blog! If you have answers for the questions I’ve raised or thoughts on my thoughts, feel free to write to me anytime. Do also write to me with feedback on this blog and whether I should keep this going.

See you again soon!

Quite an intriguing take on 'National Security'.

It would be great if you can extend the discussion through the perspective of 'Internal and External Security'.

Would love to read more, please do continue writing this blog.

And yes, please do continue writing this blog.